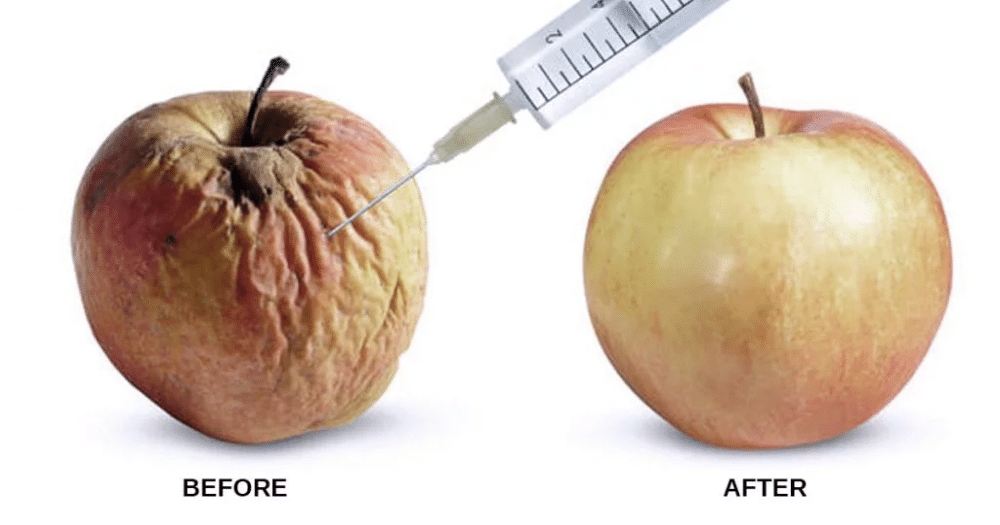

For years, Botox has been presented as a kind of modern elixir against the passage of time. A few drops of botulinum toxin, injected with millimetre precision, and wrinkles disappear. The forehead is smoothed, the eyelids are lifted, the skin appears smoother. In just a few days, the mirror gives back a rejuvenated version of oneself. But behind this chemical magic lies a much more complex reality: Botox is a neurotoxin -a substance capable of paralysing muscles and disrupting communication between nerves and tissues- and, although its medical and aesthetic use is widespread and regulated, its long-term effects on the body and mind merit further analysis.

Botulinum toxin type A, discovered from the bacterium Clostridium botulinumbegan its career in medicine to treat eye spasms, strabismus and muscle paralysis. Today it is also used to relieve chronic migraine, hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating), bruxism, overactive bladder and even some types of pelvic pain. In experienced medical hands, its efficacy is indisputable: relaxes overactive muscles and offers relief where other treatments fail. But it was its leap into the aesthetic realm that changed the course of history. Since the 1990s, millions of people around the world have turned to Botox to smooth facial wrinkles and "prevent" ageing, creating a multi-billion dollar industry and a new form of dependency: that of looking forever young.

The first injection seems harmless. A slight prick, a few days of waiting, and the face softens. The result is addictive, not so much because of the substance itself - there is no chemical dependency - but because of its psychological impact. Once the brain becomes accustomed to the rejuvenated mirror image, accepting one's natural expression becomes increasingly difficult. When the effect wears off, wrinkles and fine lines reappear and the skin loses its tension.. In the patient's eyes, it is not simply a return to the starting point: it is a sharp drop to a "worse" version, of one's own face. Thus begins the cycle. Repeating the dose every three to four months becomes an emotional routine, a way of sustaining a visual identity that no longer exists without the help of the neurotoxin.

But the body does remember. As the years go by and the injections are repeated, facial muscles - deprived of movement for so long - can become weak and atrophied. Clinical studies have documented structural changes in the treated musculature and a progressive loss of strength or elasticity. At the same time, the brain, which constantly adjusts its motor patternsThe way we perceive and use these muscles changes, in some cases resulting in a stiffer appearance or a less natural expression even after the Botox has worn off. Some patients report that, after leaving the treatment, their face "is no longer the same": the skin appears more lax, wrinkles appear in new places and facial balance changes.

At the systemic level, the risks are poorly understood. Although Botox is considered safe when administered in adequate doses and under medical supervision, there have been reports of the toxin spreading beyond the injection site, with symptoms such as generalised muscle weakness, fatigue or even mild neurological effects. In prolonged or high-dose treatments - such as those for muscular pathologies or repeated aesthetic uses - there is a possibility that the body may develop neutralising antibodies, reducing the efficacy of the product and altering its response. What is not entirely clear is how the body processes, accumulates or eliminates the biological residues of the toxin after years of constant use.

In addition to physiological uncertainty, there is an increasingly worrying trend: the expansion of non-clinical uses. Social media and influencer-driven fads have popularised exotic applications such as the ".scrotox" (injections in the scrotum to relax the skin and give a smoother appearance) or botox in the vulva and penissupposedly to improve genital sensitivity or aesthetics. These procedures, mostly without sound scientific backingThe new, more and more private clinics are multiplying with a narrative of luxury (if Cristiano Ronaldo does it, it's a trend), innovation and sensuality, but with little sanitary control and no long-term safety studies.

The price of these injections varies as much as they are intended. A facial session can cost between 300 and 800 euros, but maintaining the results requires repeating the procedure several times a year. In medical pathologies, the doses are higher and the costs easily amount to more than 1,000 euros per treatment. What is rarely mentioned is that, if the cycle is interrupted, ageing suddenly "reappears": muscles regain movement, wrinkles become more pronounced and the contrast with the previous period of paralysis makes the face look older than it really is. This rebound effect feeds the sense of loss and reinforces the psychological dependency.

It is no coincidence that some psychologists liken the continued use of Botox to a kind of induced facial dysmorphia. The patient does not look bad, but no longer recognises himself. He gets used to a filtered, frozen, expressionless image, which he perceives as his "normality". When the effect wears off, anxiety sets in. Thus, the toxin not only paralyses the muscles: it can also anaesthetise the ability to accept oneself in time.

Of course, under medical supervision and with precise indications, botox is still a valuable therapeutic tool. But to confuse a medical procedure with a cosmetic routine without consequences is a mistake of our culture of immediacy. Each injection involves altering the physiology of the peripheral nervous system.. Each repetition modifies the natural balance of the face a little more. And each session prolongs the illusion of control over ageing at the expense of an increasingly dependent relationship with a substance that, although harmless on the surface, was born as poison.

Perhaps the greatest risk of Botox is not physical, but symbolic: teaches us that the natural is unacceptable, that the gesture is a flaw, that age is a defect that can be corrected with a needle.. While the body adapts and ages, we continue to inject silence into our muscles so as not to see or show the passage of time. What does not move, does not feel; and what does not feel, sooner or later, forgets itself.